To E.B. White’s “boy from the Corn Belt” who arrived to the city “with a manuscript in his suitcase and a pain in his heart,” and for all the others who saw New York, not for what it was, but for what they wanted it to be (White, 699).

Inspiration and Approach

I have always loved books. I suppose that’s where this project came from: a love for stories that I often found were truer than the world laid out before me. I know some would characterize reading as a naive escapism. To them I say, it is these trips to others’ imaginations that make the world I stand in more inhabitable, that make the rusted nails shine on a dingy sidewalk and the crumbling red-brick buildings tower like a palace. If I live in a fairytale, refusing to abandon a childlike innocence, so be it.

I applied to the Duke in New York program because of the fairytale-like quality that I felt when I read books that took place in New York City. There was so much life there, and I felt this certainty that I would like it. For this project, I aimed to replicate the spirit of E.B. White’s Here is New York. I was particularly interested in exploring what White referred to as “Manhattan’s breathing” and how this sustaining factor of life influenced my own creative writing. This exploration was guided by field trips I took to key locations from New York City literature, including Here is New York, The Goldfinch, Let the Great World Spin, and The Catcher in the Rye. My goal was to create a written picture of New York that captured a snapshot of my New York, a New York that White described as “a fairy tale”, “a pantomime, without sound”, and a thing that “must be saved.” The majority of the writing here was written “on site”, so to speak, at the locations themselves, inspired by the excerpt I had selected from that book, and my personal experience at that place.

In one of the books, The Goldfinch, Hobie tells Theo that he never imagined that “old furniture would be the thing that decided [his] future” (Tartt, 183). Like Hobie, I would never have thought that books would lead me here, to New York. In occupying these places from the books I love, I hoped there would come a greater understanding of the book, and a wider window into the author’s vision of the world they wanted to create.

The New York Public Library, Main Branch

“I was twelve when I applied to leave. All I could see, as a boy, was everything dying. And I had this dream, this vision, of what life could be. Why be here when I could be there? I was a fool.”

– Constance’s Father in Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land

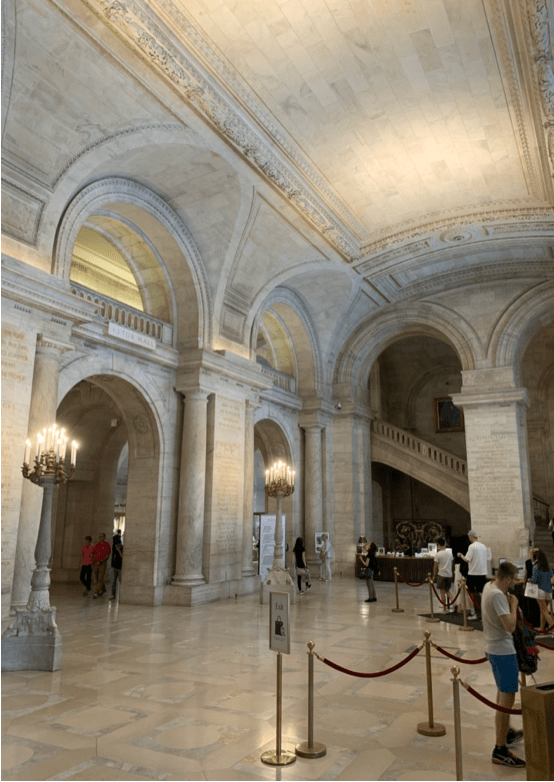

I was troubled. Again, I thought to myself, where were the books? I climbed three flights of stairs before entering a place where it wasn’t barred off, confined to researchers or staff only. I thought this was a public space—welcoming the lover of books—but so far, in the main rooms I see tourists; in the adjacent hallways, “do not enter” signs.

When I first entered the building, as I spun through the revolving door, I noticed the signature public library lion pasted on the glass—and I was filled with the overwhelming excitement that I would soon be inside of a giant library, with rows and rows of books. And yet, as I climbed the stairs, elevated myself above this initial entrance, disappointment raced through me. Where were the books?

I sit in a reading room. Three men guarded the entrance, each to inform me that yes, I was allowed to enter. Books line the walls, a seemingly lifeless adornment to furnish a workspace whose murmurs fail to possess E.B. White’s description of the library’s “great rustling oaken silence” (White, 699). The spirit of the books does not emanate outwards. It feels stagnant. Strangely, though, I face an archway—granting entry to mindless passersby— which in gold leafing avows John Milton’s words that “A good book… the precious life-blood…treasured…to a life beyond life.”

Overhead, through huge arched windows, I see Manhattan. The buildings, straining towards the blue sky, knock on the glass, and I realize that I have not escaped the city. Here, Manhattan’s breathing—its rhythm of inhalations and exhalations—does not thrum the way I thought it would. The surrounding workers feel troubled, jaded. Manhattan’s lungs struggle to take in another breath. The silence here is permeated by the constant cycle of tours—and I wonder for the nth time, if where I chose to sit ruined it all. The location we ground ourselves in grants us a permanent perception of place we can’t undo. I will never again see the New York Public Library for the first time.

I had imagined this library to be like Zeno’s Lakeport Public Library. Reading about it in Cloud Cuckoo Land, I had felt again the magic of childhood stories. It reminded me of entering the Hennepin County library as a child. It is the first library I remember. Memories rush forward: learning cursive to sign my library card; climbing onto black stools to reach the top shelves; waiting for the self-checkout station with the delightful barcode scanner; and the aisles and aisles of plastic-wrapped books that, come library day, were always lost. A great scavenger hunt to retrieve my stories; books with bent pages and scarred covers. This is what I had imagined.

Some nights I dream I’m back there. The library looks different each time, but the feeling that lingers once I have woken up, is the same. The splendor I could feel just by entering the peaked, brick building in tiny, suburban Maple Grove—and I missed home. I am reminded of Diogenes who wrote of a faraway utopia called Cloud Cuckoo Land—a story to delight his dying niece. He recorded Aethon’s entrance into this heaven-like splendor, and his subsequent decision to return to his meager shepherd lifestyle with the conclusion that “He thought of home, which no longer seemed a muddy backwater, but a paradise” (Doerr). What if my muddy backwater—the little Hennepin County Library— was more of a paradise than this ethereal marble ode to books, lifeless books that are perched on walls and never retrieved, ever could be? I am reminded of Constance’s father, who, opting to leave his wonderful home on Earth for an experimental trip to another planet, ultimately concluded, “I was a fool.” What had lain in front of him was greater than the promise of what lay ahead.

Now, I sit on a wooden bench, facing away from the famous Rose Reading Room, back turned to the worker bees, the diligent ants arrayed at perfect distance. Here, the wood feels right: steady, firm, unforgiving. It invites a weary traveler: sit here, book in hand, open me as you are, I am as I am. I am tempted to pull out my book, Catcher in the Rye, to escape into Holden’s depiction of the city, a picture of NYC that seems truer than the one I view from the public library. In his created world, things seem most true. And yet, it is fiction.

Perhaps the imagination will be truer than these fine marble walls ever will be. No life is breathed back into the building. The walls grow ever shakier, a book is plucked off the shelf and the shelf tumbles.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dutch Masterpieces

“Isn’t it amazing? The first painting I ever really loved.”

– Theo’s Mother in Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch

I came upon the “Dutch Masterpieces” exhibit by accident. I had been searching for the American Wing Cafe, a place to sit down to read my excerpt from The Goldfinch, and of course, was hopelessly lost. My first detour had been through the world of the Ancient Egyptians.

I sit in a giant room, ladened with tourists, and in the center of all the madness, a tomb. Sanctioned from the 90 degree heat, natural light floods in from floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking Central Park. The exhibit is Egyptian. The tomb resides in the museum, memorialized, for the sheer fact that, after all these years, it is still here. Not because of a careful hand imprinting intentional details, but because of existence. The piece does not resonate with me. The space of this room, though, I like. What opulence, to demand this much space for a relatively small display.

I continued on. Even after asking for directions, I still had yet to find the cafe. Like Theo and his mother, I was wandering through busy galleries, “weaving in and out of crowds, turning right, turning left, backtracking through labyrinths of confusing signage and layout” (Tartt, 23), and then, I stumbled upon it. Scrawled on the wall, a floor below, I could just make out the title “Dutch Masterpieces.” Knowing that Theo and his mother, on their trip to the Met, attended a Dutch painting exhibit, I felt obligated to go down and check it out. However, I, like Theodore, was “not very excited at the prospect of a lot of pictures of Dutch people standing around in dark clothes” (Tartt, 23).

On the floor below, there were, of course, lots of paintings of dark clothed-Dutch. The last hallway, though, intrigued me: still lifes, or as Theo’s mother called them, Nature Morte, “Death in Life” (Tartt, 24). According to the description on the wall, these Dutch still life paintings were part of the Met’s Founding Purchase of 1871. I had walked through an entire room of dead birds and sullen looking men before winding my way back to where it all started: the paintings that had been here since the very beginning.

Ahead, hangs a painting, oil on wood, that is dwarfed by its nearby neighbors. It is small, simple, and yet I am drawn to it. The note on the wall labels De Heem’s “Still Life with a Glass and Oysters” as “diminutive” and thus intended “for a single viewer.” Strange, I thought, how the dimensions of the painting could dictate the audience size it ought to have. Despite its tiny frame, there are details. The scene was stroked by an intentional hand, perhaps of the same Dutch blood that created the microscope, and thus, as Theo’s mother concluded, “Even the tiniest of things mean something” (Tartt, 23).

Within the frame lie some of the essential characters of still lifes: a knocked over glass, peeled citrus fruit, seafood. These objects were first meant to represent vanity, and then, to signify luxury (“In Praise of”). Staring at the painting, my eye is drawn to the yellow, and I wonder, how did the lemon peel come to be a quintessential aspect of the still life? An unwinding string, protecting the softness within, stripped, and dragging to the floor, tugged to the ground, ground to dust, to death, apart.

In its neighboring painting, the sullen lobster lies unmoving, and a cantaloupe rests with enlarged seeds. The thick oil paint attracts the glare of the gallery lights. Each painting, from afar, is dark, but as you come closer, it is clear that there is contrast. Despite the narrow focus of color, the scene comes alive.

I’ve never really written about art before, but the way in which Theo’s mom spoke of it —so lovingly—made me return to stare at this little painting again. I stood with a greater appreciation, searching for “stillness with a tremble of movement” (Tartt, 23), and felt much love for that little painting. I had never fallen in love with an art piece before, but I suppose, neither had Theo, and he spent his whole life protecting “The Goldfinch.”

At an upstream painting stand two very impatient kids, unsuccessfully trying to escape their father’s lecture—about art, I assume. I am transported, back to the excerpt from The Goldfinch: “the echoing halls” that turned “to carpeted hush”; the exhibit’s “meandering feel of a backwater” with “long sighs and extravagant exhalations”— breaths that sighed long and hard because they had the space to. And I realized, in that narrow hallway, that I, like Theo’s mother, was oblivious to time flying (Tartt, 24).

Upper East Side Apartment, E 76th St and Park Ave

“Claire had told them, at the first meeting, that she lived on the East Side, that was all, but they must have known, even though she wore long pants and sneakers, no jewelry at all, must have intuited anyway, that it was the Upper East Side, and then Janet, the blonde, leaned forward and piped up Oh we didn’t know you lived up there.”

– Claire in Colum McCann’s Let the Great World Spin.

Park Avenue, even as someone who had yet to reside in the city, carried with it the gilded indication of wealth. Up there. The Upper East Side, or as Claire tried to simplify it—The East Side. It reminded me of Malcolm in A Little Life and his efforts to force a certain perception of himself by instructing the taxi of either “Park” or “Lex,” depending on the impression he wanted to imprint on the driver.

In Claire’s opinion, her penthouse living forged a physical barrier between her and her support group of women. “Up there”, she says in distaste, “As if it were somewhere to climb. As if they would have to ascend to it. Ropes and helmets and carabiners” (McCann, 77). Claire’s effort to relinquish this mark is, while understandable, rather pointless. Her wealth radiates in other ways, from her wish to “hire” one of her friends, to her concern that the doorman will mistake her shabbily dressed friends for hired help.

Walking on Park for the first time, in the lower 90’s, I was struck that the buildings there did not look much different. There was no variation from Lexington to Park, at least on the exterior. Buildings built, perhaps by the same architect, yet wildly different, distinct, in price and social perception. And then I realized the difference—it was quiet. Quiet, in New York City, from one street to the next. I could hardly believe it. Was what you paid for—in a city of constant motion—silence?

Unlike my other field trips, I could not go to the place itself. The closest I could get was walking along Park and standing on a rooftop overlooking the Upper East Side. Instead, I read this excerpt from my apartment on the East Side, the East Village, however, a far cry from Claire’s sheltered streets. For this experience, I will only ever be on the outside. This one forces imagination: to be elevated above, the top floor, a palace—a fairytale, or perhaps a nightmare.

Woven of softened voices and thicker walls, the energy of Manhattan has morphed here. And yet this is the ideal—right? To live here after working for years? A little suburbia on the edge of the city; to desire somewhere close to the madness, but distinctly removed. I wonder, how does Manhattan breathe here if the inhalations are muffled by some magical invisible barrier that cocoons the streets? It is a different kind of breath, slower, with a lack of urgency, the quiet hum of family life. Perhaps it calms you, to return to the madness once again. Up here, like a heaven. Little black squares, or windows aglow on reddened buildings, the city already asleep.

The Central Park Carousel

“I felt so damn happy if you want to know the truth…God I wish you could’ve been there.”

– Holden Caulfield in J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye

Let me tell you, Google Maps does not function well in Central Park. I was just about ready to give up and abandon my attempt to find the carousel when I walked head into it. Ah, there it was.

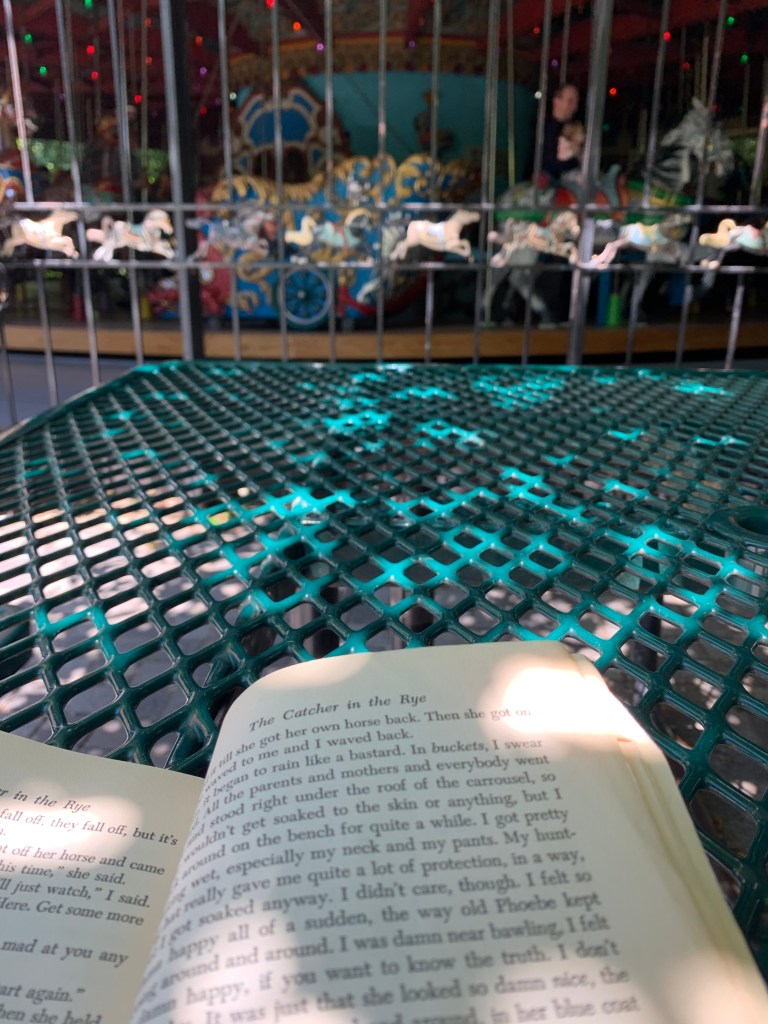

I sit down at a green picnic bench facing the carousel, pull out my copy of Catcher in the Rye and my headphones, and push play on the song “Oh Marie.” In the book, Holden sat on a bench, watching his younger sister Phoebe ride the carousel, and listened to this song. As I open my book to the closing scene of Catcher in the Rye, the singer calls out “Oh Marie, Oh Marie,” and I am taken away, straight into the story.

Wooden horses race happily in circles. Teeth open, pulling against the bit, decked out in royal blue jackets and dark green bridles with gold buttons. Based on a long ago game for knights, the hand-carved horses now rise up and down in a simulation of galloping (“History of Carousels”). The carousel that spins before me is the fourth of its kind in Central Park. In 1871, the carousel was powered by a mule, and the next two were destroyed by fires. Holden’s carousel burned down in 1950, and now there are no more golden rings to reach for (“Central Park Carousel”). Housed in a brick building, these horses were a devil to find, but they did not disappoint. The child’s joy exists here. It wasn’t phony, as Holden would say, it was real.

Watching the carousel is making me dizzy, but I don’t want to look away. Little kids with their proud fathers, hands on backs to keep them from sliding off the horse, to keep them safe. It’s father’s day—I’d forgotten that. One girl, maybe eight or nine, is the oldest on the ride, aside from a few stray parents. She rides, so happy, looking ahead to her father as each turn of the carousel brings her a little closer to him. Next to him, other parents wait on the outskirts: off the carousel, just like Holden, just like me. Part of me wanted to get on the carousel, hop in line, buy a ticket, search for the rustiest horse on there, just like Phoebe; to feel what it would be like to be her, too big for the horse, but still there, delighting in the repeated spins.

The music plays again and again, still ringing even as the carousel slows to a stop. I feel as Holden did, so damn happy. Perhaps it wasn’t the children’s faces that did it, it was their parents. The proud fathers, unencumbered, radiating joy, so unusual for a grown man. Brought on by the joy of a child, or perhaps, an excuse to return to the carousel again, even though they know they’re too big. To turn without having to move forward, to be the catcher in the rye, to stand there and save all the ones about to fall off the cliff—that was the only thing Holden really wanted to do. Delighted by the scene in front of him, he sat, even as it began to pour. If it had started raining right then, I think I would have stayed. God, I wish you could’ve been there.

I sit, later that day, in Central Park. To my right, young kids play tag, arms outstretched, in a never ending circle. Oh, I remember, I was once that young. I could play tag for hours and the days felt like they stretched on forever. So many “Daddy’s” ring through the park today. The gentle education of a father teaching his son to throw a football, children gathered around their father in his lawn chair. The knit, the bond between father and child, is closely tied today. Nestled within the very center of the park, in the center of the city, Manhattan breathes a little softer here.

Today, I am as Holden, an observer. Like me, he had no tolerance for phoniness. In his search for truth, he found it again, watching a carousel, a thing of child’s play. I don’t think that is a coincidence. A carousel, like a fairy tale, was a simulation, a distraction. On and on the horses carried you but you never really went anywhere. That was the joy though—you were suspended in a moment, life moving around, without being forced to move forward.

—————————————

E.B. White, after writing of the fairytale-like nature of Manhattan in Here is New York, went on to write children’s books. After experiencing New York, he imagined make-believe stories for children, to delight them in all their innocence and unencumbered joy. I think, then, there is something to be said about the imaginative capacities of New York. In the rhythm of Manhattan’s breathing, there exists the wisps of a fairy tale.

The city, White said, “is like poetry, it compresses all life.” I am reminded of the citrus fruits unwinding in a still life; Holden sitting in the rain overjoyed to be watching the carousel spin again and again; Claire cocooned in her penthouse picking out her dress, and jewelry, and five fine china teacups—and I realize, life has escaped the compression.

With all the movement of New York, these stories could get lost in the whirl, but on the 4 train to work, as we charge underground, through the city, it slows down. I sit across from a blue-suited top-hatted man who stands next to a mother gripping a stroller, her baby staring wide-eyed at me. They are all unfazed by the changing speeds, the occasional stop. They are in motion, on their morning and evening commutes, they travel, in circles, in New York, New York.

Works Cited

“Central Park Carousel.” Central Park Web, https://centralpark.org/carousel/. Accessed 24 June 2022.

Doerr, Anthony. Cloud Cuckoo Land. Simon and Schuster, 2021

“History of Carousels.” History of Carousels. http://www.historyofcarousels.com. Accessed 24 June 2022.

In Praise of Painting: Dutch Masterpieces at the Met. 16 Oct, 2018- Present, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

McCann, Colum. Let The Great World Spin. Random House, 2009.

Salinger, J.D. The Catcher in the Rye. Back Bay Books, 2001.

Tartt, Donna. The Goldfinch. Back Bay Books, 2015.

White, E.B. Here is New York. Harper & Brothers, 1949.

Leave a comment