The Nine Muses of Greek mythology were often invoked by men heralded as the greats of literature. The authors sought divine inspiration to craft wonderful works that would yield them earthly acclaim. The sheer propensity of the muses’ invocation could be taken as flattery, but instead of recognizing women as uniquely creative and imaginative, they only mentioned the muses when they, as men, wanted something. The muse’s entrenchment into servitude echoes their origin story, in which Zeus, Greek God of gods, harassed their mother into sleeping with him for nine consecutive nights. It seems that despite their popularity, a muse has undeniably been prescribed inferiority. A muse is not intended to inspire the self, but to yield to someone else’s manipulation of art.

Growing up as a girl in the early 2000s, there were obviously times where boys insisted on maintaining the rhetoric that boys could do things that girls couldn’t. I was told I needed a new backpack because red was a boy’s color, and that I couldn’t play kickball at recess because that was for the boys. For the most part, though, I grew up thinking I could fit into any place I wanted. That being said, while I wasn’t directly limited, I also don’t remember many examples of a woman being bold, headstrong, or powerful, and being loved for it. I grew up on the demure Disney princesses and the virginal Catholic saints—they were supposed to be my idols.

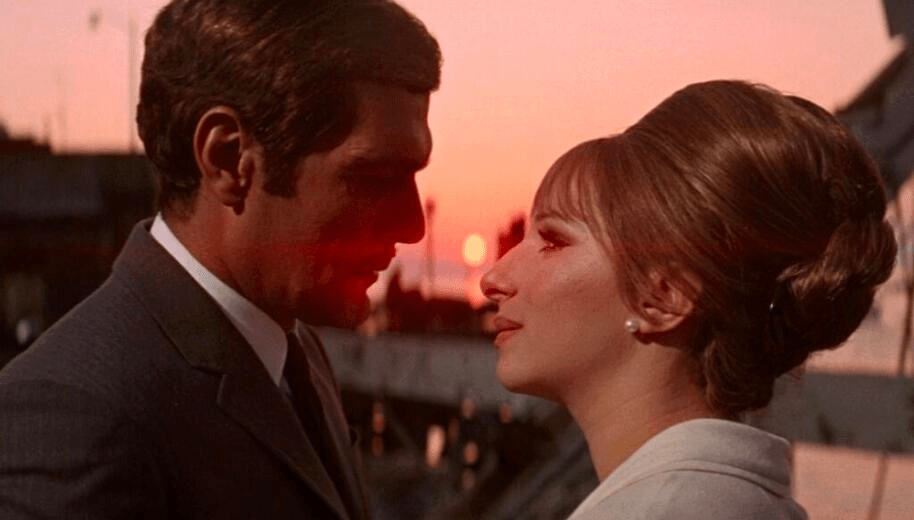

I was nine the first time I was introduced to Funny Girl, a movie adaptation of the 1964 hit Broadway musical of the same name. Watching with my dad one day after school, I was instantly hooked, transfixed, as lead character Fanny Brice made her break in the New York theater scene. It was simultaneously her story, and her love story with a man whose manhood was ultimately challenged by her stardom. At that age, I didn’t understand the complexities of their relationship, and even after watching the movie so many times that I can quote dozens of lines, I still am not sure how I’m supposed to walk away feeling. At the time though, I think some subconscious part of me recognized that this was something special—a woman, defiant in her belief that she was talented, tracking down success, and in the process, a man, too. That’s what I wanted.

I’m the Greatest Star

Within the first fifteen minutes of the movie, we see Fanny being cut from an audition for not being pretty enough. Her appearance is further ridiculed as the director asks the stage agent if he “owed somebody a favor.” Undaunted, Fanny argues with the stage agent, reasoning “I’m a bagel on a plate full of onion rolls, no one knows they want me, because no one’s tried me!” Her protests were ignored and she is forced to abandon her attempt as she is ushered outside. Only temporarily stymied, she quickly declares “I’ll get what I want, I know how” and marches back into the theater to sing that “in all of the world so far,” she is after all, the “greatest star.”

Watching this scene, even now, I still can’t quite understand how Fanny could be so confident in her talent that she was comfortable exhausting all her arguments, pleading in desperation, just to get on the stage. She was undeniably certain that she had something, something that needed to be shared, and despite a continuous stream of rejections, she didn’t give up.

His Love Makes Me Beautiful

Shortly after her testimony to the director, Fanny’s determination pays off, winning her a theater act in which she attracts the attention of Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld. Despite his outstanding reputation, and her previous promise that she will “do whatever he wants,” within the first minutes of being on set, Fanny argues with him, imploring him that it would be best if she chose her own songs. Fanny believes that the song he assigned her, which features a bride who is beautified by her husband’s love, would sound ridiculous if she, who is clearly not picture perfect pretty, sang it. The audience would laugh at her if she sang lyrics like “a walking illustration/of his adoration.” Ziegfeld, however, does not care.

Although she loses this battle, on the night of the opening performance, Fanny, in a last minute moment of inspiration, alters her costume so that she appears in a bridal gown in “the family way.” The audience delights in this subversion of the usual propriety of the theater, responding to her humorous modifications with unadulterated laughter.

Once again, Fanny is unquestionably bold, risking her career to protect her belief that she ought to be comfortable with the topics she is singing. Importantly, she didn’t make this change to spite Zigfield, but, as she said, “it just came to her.” While the audience laughed at her, which was her initial fear, they were laughing because she “wanted them to laugh,” and that made all the difference. In this scene, Fanny took ownership of her values and of her creative talent, and, inspired by the pillow in her dressing room, turned a respectable audience into raucous laughter.

Don’t Rain On My Parade

As the movie progresses, Fanny catches the eye of wealthy Nick Arnstein who has made his money from being exceptionally good at gambling, whether it be from poker or panning for gold. He is polite, charming, and most certainly, in love with Fanny—at least in how she shows up on the stage: confident and undeniably talented.

While on tour in Baltimore, Fanny and Nick meet again, and this time, Fanny doesn’t want to say goodbye. In the week she spends with him there, Fanny remarks “I’ve been to Baltimore loads of times before, but I never realized it was the most beautiful city in the world.” Nick’s uncustomary and frivolous lifestyle, in such stark comparison to Fanny’s modest upbringing, tempts her to abandon all that she has gained on the stage, in return for his love. In her famous “Don’t Rain On My Parade,” Fanny abruptly decides to leave the tour, and instead, follow Nick to Europe. Her friends protest, struck by her defiance, and advise her that she can’t just drop everything for a man. She doesn’t care though, she wants to live life to the fullest, and tells them off, singing “don’t tell me not to fly, I’ve simply got to.”

Fanny carried her tenacity and certitude into her love life, not being shy or trying to save face and her pride. She knew what she wanted, and damn it, she was going to pursue it.

Funny Girl

In Fanny’s debut of Swan Lake, Nick is nowhere to be seen. Instead, he spends his night at his friend’s casino, trying to make some money, as he is unable to accept that she provides more than he does. Later in the night, Nick, uncomfortable with her success on the stage, and his own monetary failure, risks it all in a corrupt business deal. At this point in the movie, Fanny has achieved all she ever wanted. Everyone adores her, on and off the stage. She recognizes this success, singing “Funny. Did you hear that? Funny.”

And yet, she is unhappy, because she doesn’t have her man anymore. In his attempt to rescue his manhood, their love seems to be slipping through her fingers. In one of the most heartbreaking lyrics, Fanny remarks that “And though I may be all wrong for the guy, I’m good for a laugh.” Being funny has become Fanny’s identity, being funny is how she has made a name for herself, but at home, when she is no longer protected by the bounds of the stage, when she no longer wants to act the part of “funny,” she is expected to relegate herself back into her submissive role as a wife. When she doesn’t do this, the marriage begins to fail.

The movie ends with, presumably, the couple going their separate ways, but Fanny ends singing that she will be “his, forevermore.” Here, her stage persona seems to falter. She is infallible, breakable, and more than just “funny.” I have never been sure how to take this. Did she love him, even if she recognized they shouldn’t be together? Perhaps the fact that she is singing, utilizing her own creative talent, should give me confidence that she retained her creative pursuits outside of love. And yet, the fact that she ends singing about a man, that that’s the last we hear from Fanny, seems to centralize a characteristic of softness that contradicts her bold nature. He tried to keep her down, and when she protested, she lost him. While she may have retained her success on the stage, this bittersweet ending seems to suggest an undeniable loneliness for a woman who doesn’t want to be your muse.

——————————

Women who are muses are expected to serve, not in the traditional homemaker role, but as inspiration, for others to take the rights, to profit. In Funny Girl, I saw for the first time a woman who was her own muse. She inspired herself, ran the show, quite literally, and paused for no one. In tenth grade, my English teacher applauded me for my general disregard for our 17:3 male: female ratio, as my willingness to speak my mind, regardless of the audience, was something she wished she had mastered by my age. As someone who had been described as aggressive, stubborn, and just generally a bitch, I was once again struck, like when watching Funny Girl, that these labels could transcend their negative connotation, and instead, fit under the identifiers of “powerful” and “strong willed.”

Watching Funny Girl growing up, Fanny’s role grew to more and more importance for me. Traditionally, the play is described as a testament to the fact that you don’t have to be pretty to find success. While this may be true, it is so much more than that. From her obstinance to “get what I want, I know how,” to going as far to claim she could roller skate when she had never before laced up skates, Fanny knew the stage was her place. The stage was her home to take refuge in, she just had to get on it. Refusing to bend to the creative license of anyone else, in all that she did, Fanny exuded a confidence that was unapologetically her, unapologetically female.

In Greek mythology and beyond, muses are confined to the back seat of the car racing towards success. They unfurl the red carpet for the creators to glide to the golden medals and formal recognitions, and are unceremoniously tossed aside the moment they stop inspiring. It is a role of submission that I first saw Fanny Brice refuse, and I, like her, don’t want to be anyone’s muse.

Leave a comment